Humans like to think of ourselves as the only animal that speaks to each other using language. It’s one of the things that “separates us from the animals,” so the saying goes. However, we already know that lots of other animals communicate with each other using vocal-auditory communication. Further, we’re beginning to learn that other ape and monkey species use distinct words and phrases with unambiguous meanings. In other words, they have vocabulary, which is among the basic requirements for language development.  Human speech, however, is definitely a cut above other animal modes of communication. It has grammar, tense, mood, and elaborate phrasing relationships that open limitless possibilities for expression. Importantly, speech itself is not required for all of this communication richness; sign language has it also and some anthropologists believe that gestural language developed in humans before spoken language. Aural and sign language are processed by the brains similarly.

Human speech, however, is definitely a cut above other animal modes of communication. It has grammar, tense, mood, and elaborate phrasing relationships that open limitless possibilities for expression. Importantly, speech itself is not required for all of this communication richness; sign language has it also and some anthropologists believe that gestural language developed in humans before spoken language. Aural and sign language are processed by the brains similarly.  Our very anatomy has evolved to accommodate and enrich our speech. Many of the sounds that we make, particularly vowel sounds, cannot be made by other apes. Their throats are too shallow and their voice boxes too high. In the ancestry lineage of human evolution, the adaptation of our throat anatomy to facilitate speech (as we know it) occurred quite recently.

Our very anatomy has evolved to accommodate and enrich our speech. Many of the sounds that we make, particularly vowel sounds, cannot be made by other apes. Their throats are too shallow and their voice boxes too high. In the ancestry lineage of human evolution, the adaptation of our throat anatomy to facilitate speech (as we know it) occurred quite recently.

The fossilized remains of Homo habilus, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and others, exhibit a throat structure closer to other apes than to humans. It is unlikely that they could speak as we do. What about Neanderthals? Neanderthals are our closest cousins, separated by 500,000-700,000 years of separate evolution (with some interbreeding, especially toward the end of Neanderthals around 50,000 years ago). If any non-human species could speak, Neanderthals would be the most likely candidates.  The common perception of Neanderthals is that of brutish dimwits who communicated by grunts and growls. This characterization could not be more wrong. Neanderthals lived in social communities with a complex lifestyle. They wore clothing, made jewelry, used tools, hunted big game in a coordinated fashion, and made drawings on cave walls. They even buried their dead (and some maintain that they did so with trinkets and ornamentation, indicating funerary customs, a telltale sign of religious belief, though this is controversial). Neanderthals even had bigger brains than we have, though that does not mean that they were more intelligent.

The common perception of Neanderthals is that of brutish dimwits who communicated by grunts and growls. This characterization could not be more wrong. Neanderthals lived in social communities with a complex lifestyle. They wore clothing, made jewelry, used tools, hunted big game in a coordinated fashion, and made drawings on cave walls. They even buried their dead (and some maintain that they did so with trinkets and ornamentation, indicating funerary customs, a telltale sign of religious belief, though this is controversial). Neanderthals even had bigger brains than we have, though that does not mean that they were more intelligent.

But did they speak and use language? There has been no discovery of Neanderthal writing, but that doesn’t really say anything. Humans didn’t invent writing until a few thousand years ago, despite having a spoken language for hundreds of thousands of years. Our brains are hard-wired for language acquisition through listening and speaking, not reading and writing.

Children spontaneously learn to speak, but they have to be arduously taught to read and write. So how can we ever know if Neanderthals spoke? One line of evidence is the anatomy of their throat. Speech, at least as we know it, depends on certain anatomical arrangements.

The throat of the modern human is not the only arrangement that would allow speech, but it does teach us about what kind of sounds can spring from different tissue architecture. Research into the relationship between anatomy and speech in extinct species centers around a few bones in the throat. Bones are our only resource for these questions because soft tissue does not fossilize well. (It doesn’t fossilize at all usually.)

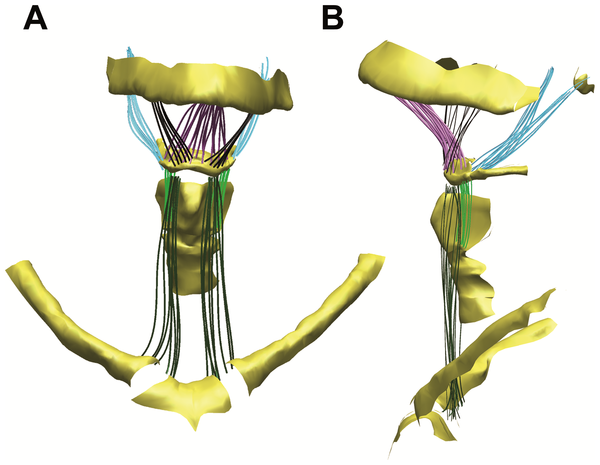

The hyoid bone is a semicircular bone located high in our throat. It’s quite strange, as bones go, because it is not firmly attached to other bones. Instead, it is the central anchor for a variety of muscles in the throat, face, larynx, and tongue. As such, it is central for the formation of sounds, as well as swallowing, gagging, coughing, and other things we do with our throat.

Although scientists haven’t reached complete agreement about the precise role of the hyoid bone in the formation of the rich variety of sounds that various hominids can make, the hyoid definitely does tell us something about the structural and spatial arrangements in the anatomy of the throat. If we also have the jaw bone and larynx, scientists can often deduce what kind of sounds an animal can make.

Several Neanderthal hyoid bones have been found over the years, and scientists from the University of New England recently analyzed them using high-resolution X-rays and three-dimensional computer modeling. This allowed the scientists to see inside the hyoid bone as well as subtle features on its surface, which indicate points of attachment to the various musculature.  From this, the scientists were able to conclude that the hyoid bone was as low in the throat of Neanderthals as it is in modern humans. Since we know that the hyoid bones of what we believe is our common ancestor with Neanderthals is much higher, this is an example of convergent evolution.

From this, the scientists were able to conclude that the hyoid bone was as low in the throat of Neanderthals as it is in modern humans. Since we know that the hyoid bones of what we believe is our common ancestor with Neanderthals is much higher, this is an example of convergent evolution.

Both humans and Neanderthals experienced a steady drop in the position of their hyoid bones. Does this mean that Neanderthals could speak like we can? No one can say for sure, but this is definitely a strong piece of evidence that they could. It is fascinating to ponder Neanderthals conversing with one another in a rich language of sounds not unlike our own.  This is also a nice reminder of how much speech benefits survival and success. Both humans and Neanderthals experienced the same anatomical change in their throats in a relatively short amount of time. This means that the selective pressure was strong. Individuals who could speak more clearly and elaborately left more offspring than those whose speech was more rudimentary.

This is also a nice reminder of how much speech benefits survival and success. Both humans and Neanderthals experienced the same anatomical change in their throats in a relatively short amount of time. This means that the selective pressure was strong. Individuals who could speak more clearly and elaborately left more offspring than those whose speech was more rudimentary.

Speech also goes hand-in-hand with intelligence. It’s probably the most cognitively advanced thing that is hard-wired into our brains. In fact, most anthropologists agree that the “great leap forward,” which ushered in the modern era of human existence, was due to the final cognitive advances that allowed complex language.

The great leap forward occurred between 50,000 and 75,000 years ago in the lush fields of the African savannah. The Neanderthals might have made that leap before we did. If we are unlocking the secrets of their hyoid bone correctly, Neanderthal anatomy developed for speech before Homo sapiens did. While our cognitive development undoubtedly surpassed theirs later, there is good evidence that they were speaking with elaborate language before we were.

Indeed, this seems likely because their artwork is older, their funeral rites are older, and they developed advanced tools before we did. This is just one more piece of evidence that Neanderthals were nothing like the ignorant brutes they are often portrayed as.

-NHL (@nathanlents)

Reblogged this on a political idealist..

LikeLike

Modern Man carries Neanderthal genes so if gene mixing occurred, communication between modern man and neanderthals must have occurred. Their height and neck muscle mass may have changed sounds and it might have been similar to people learning a new language and have an accent and cannot pronounce certain sounds eg. TH in english. Language exchange must have occurred, i think.

LikeLike

Nathan, thanks for the blog. I don’t think the Neanderthals could speak nearly as well as we can because their facial anatomy, being “over-sized” in relation to us, prevented them enunciating clearly, therefore precluded clipped words. Words are the building blocks that allow very complex communication. The position of the hyoid bone is a function of gravity so it arguably only shows that they were upright as we were.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment. I agree that the ability to speak involves much more than the hyoid bone and further agree that Neanderthal “speech,” if such a thing even existed, was likely very limited and rudimentary compared to ours. Their anatomy speaks to that, but so also does what we know of their behavior, which is much more like archaic Homo sapiens, who also probably didn’t use complex language, than fully modern H.S. (post-great leap forward). But the Neanderthal hyoid is different than other fully upright hominins, and this raises this possibility that they had a greater vocal range than predecessors including heidelbergensis. Archaic humans had the lower hyoid also, but didn’t use complex language (we believe), so speech is clearly more than the hyoid. However, I think they were well on their way, making a rich variety of sounds, calls, and probably words. That seems likely to me given what we know to date. Thanks again. It’s questions like this that really make me wish I had a time machine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s that popular trope by which Neanderthals wandered about uttering phrases about their base needs in the third person (‘Grorg Want Wo-Man’, ‘Throg Bring Meat’, etc), but for me the question isn’t whether their communication was ‘complex’ by our standards, but whether it was effective? In my country of New Zealand, for instance, Te Reo Maori – a language with a deceptively ‘simple’ range of phonetic variations, early Missionaries attempting to transliterate it selected only 20 alphabetic characters (including 2 diagraphs). In fact Te Reo is a sophisticated language capable of communicating anything very effectively, and with the most delicate and complex nuances anyone could wish for.

The issue boils down, I suppose, to assumptions about Neanderthal cognitive organisation. You suggest, axiomatically, that ‘our cognitive development undoubtedly surpassed theirs later’, which is a standard position, and I don’t directly disagree – but it would be nice to get some empirical data (that elusive time machine! :-)) My suspicion is that we’d potentially be surprised, were we to meet one – just as we’re getting surprises from far more distant relatives such as chimps.

I discovered your site, incidentally, as part of work I’m doing on the 19th-20th century intellectual framework of evolutionary theory. Good stuff.

LikeLike

Samoan is a language derived from South East Asia but differing in that vowels are the key and consonants much less important and capable of being substituted somewhat without changing the meaning of the word. Despite this, the majority of the Samoan culture is expressed in a very subtle, rich and expressive language with art and customs to a degree subordinate to the language. This would argue that the clipped speech that we English speakers think is necessary may not be the so essential.

LikeLike

Is it possible that the position of the huoid bone in humans is a result of interbreeding with Neanderthals rather than convergent evolution, since you mention that Neanderthals had it first?

LikeLike

Well Neanderthal genetic legacy has only been seen in Eurasians. Africans don’t have history of Neanderthal interbreeding as far as we can tell. Yet hyoid is the same in all. Argues against Neanderthal as source of this, but interesting idea. Our lineage surely interbred with other Homo lineages along the way. Who knows what alleles and variation were shared?

LikeLike

That would not account for the fact that the people in Africa, that never had a toss in the hay with Neanderthal, have hyoid bones located such as to allow for complex language.

LikeLike

This is a very interesting article by Nathan H Lents. I noticed that the way in which he used the word human seemed to be exclusively in reference to H. Sapiens, to the exclusion of H. Neanderthalensis. My understanding has been that creatures in the genus ‘Homo’ were humans, albeit a different species (or in the case of Neanderthal, a different sub species, depending on who you ask).

LikeLike

Evolution’s. not so, and don’t you dare say it’s so.

All creatures were created by Jesus in the first 6 days.

Can evolutionists cite a single line of scripture that supports evolution?

Didn’t think so.

I am not opposed to science – REAL science.

I did an empirical test of evolution – several in fact -and they unambiguously FALSIFIED evolution.

For example, I growed up on a farm, with a whole bunch of critters.

Horses, Cows. Hogs,

In over twenty years of experience, not a one of them evolved.

Now, evolutionists would have assumed that in all that time, at least one of them critters should have ‘evolved’ into some other critter.

Nope.

So EVIL-ution HAS BEEN falsified.

And all y’all liberals and Jessus deniers KNOW. this.

But y’all won’t admit it.

Fun fact: Folks what are influential in media and banking generally support EVIL-ution.

Just sayin.

LikeLike

Lol this is so sarcastic that I can’t tell if it’s sarcastic! If not, sorry dude, move on. If so, well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe this sounds bad but wikipedia says that whether or not Neanderthals had symbolism/complex burials jewelry etc. is contested. I’d like to imagine a lost history of stories and characters but I’m not sure.

LikeLike

Yes, it is definitely contested. From the hundreds of thousands of years that Neanderthals roamed Eurasia, we have precious few artifacts to tell us how they lived and died.

LikeLike

Divine peace be upon truth seekers. I am an orthodox Muslim electrical engineer from Pakistan. Today I found an agnostic listening to the Recited Logos of Quran for the first time and he chose Chapter 55 and its very 4th verse talks about learning and teaching of language, but as the word recitation tells us, oral expressions also fall in the category of bayan or self-expression. The title of this article is exactly the question that came up in my mind after I read verse 4. Thanks for writing. I was happy to read about Neanderthal funerals because our Scripture also talks about corvid mourning.

LikeLike

Could Homo sapiens have possibly learned things such as controlling fire and speech from Neanderthal man when first we encountered them in Europe?

LikeLike

I have little doubt that sapiens and neanderthals exchanged some skills and other cultural memes. As for fire, hominins had been working with fire for a long time before the european sapiens-neanderthal reunion. It’s likely that both populations had a long history with fire but I think it’s likely that they learned cooking/rendering skills from one another. Thanks for your interest!

LikeLike