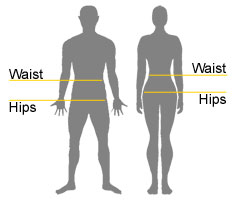

Around the globe, across cultures, and throughout history, one physical feature has stood out as consistently correlated with attractiveness in females: waist-hip-ratio (WHR). The desirability of a low WHR often cuts across other preferences in body size and shape both among individuals and in cultural predominance.

Attractive waist-hip-ratios (WHR) can come from a skinny waist, wide hips, big posterior, or any combination thereof. Of course, “attractiveness” is something that is deeply personal, highly subjective, culturally influenced, and impossible to fully articulate. Nevertheless, the attractiveness of a low WHR has held up in many cross-cultural studies (though it is definitely not universal among individuals anywhere).

Interestingly, the preference for a low waist-hip-ratio (WHR) is not purely sexual. When studies have asked participants to rate female bodies on attractiveness, both heterosexual women and homosexual men mostly mirror their heterosexual male counterparts in identifying a low WHR as attractive, even when they are divergent in how they rate other physical features. All of this speaks to some kind of ingrained preference or instinct, but why would that be?

Most theories have focused on WHR as an indicator of health and fertility. Indeed, in both males and females, a low WHR does correlate reasonable well with cardiovascular health and longevity, while a high WHR puts us at greater risk for diabetes and even autoimmune diseases and cancer. While the average ratio is different in men and women, the correlation to health holds. In women, the best health picture is found in those with so-called “pear-shaped” body proportions. While in men, the ideal ratio is achieved by minimizing belly fat. For both men and women, WHR is a better measure of health than weight alone, BMI, or physical fitness.

In women, the connection between WHR and health measures appears to be hormonal. It is known that ratios of estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin affect all of these features. The “right” balance promotes both health and low WHR. One version of the “attractiveness theory” posits that our attraction to this body shape developed as an indicator of overall health.

As I wrote previously, certain vocal features also correlate well with low WHR in women and, you guessed it, these vocal features are present in voices that most people rate as attractive. Once again, hormone ratios seem to be the connection. The effect of a “good” hormone balance can be detected in vocal features as well as body shape.

Other studies have found that we are even capable of smelling our way toward this favorable hormonal balance.

Another crucial part of the attractiveness theory of wait-hip-ratio (WHR) is that this body shape has to be indicative of something related to fertility, or else it wouldn’t have any evolutionary value. The key feature in a potential mate is biological fitness, that is, the potential to give birth to many healthy and successful offspring.

Desirable females, in the evolutionary sense, are those that are likely to be healthy, fertile, and robust. A low WHR, it is thought, must correlate with fertility (ability to have children) and/or fecundity (tendency to have large numbers of children).

Attempts to establish this relationship have given murky results. Some studies have found a connection between low WHR and fertility, but others have not. Furthermore, it is not always possible to separate fertility from health. Women in better health tend to have more children than those with chronic help problems. So the question is, does our attraction to low WHR have anything to do with fertility?

(As an aside, there are also theories to explain the attractiveness of male sexual characteristics. However, the paths toward biological fitness were probably quite different for males and females during the time that our species was evolving. In any vertebrate species, females are limiting for reproduction and males are mostly expendable. This places different kinds of sexual-selective pressures on the two sexes. For example, in many (but not all) mammal species, there is some degree of male-male sexual competition. Female-female sexual competition is much less common and, when present, takes different forms. Universally attractive features for men are height and facial hair, but social considerations, such as power and position, seem to be more important for men than for women. Attractiveness in men has been shown to correlate with levels of testosterone, for example, but this does not connect to WHR and requires a great deal of caveats since levels of testosterone also correlate with likelihood of ending up in prison. The point here is that attractiveness in men seems to follow a different set of rules, so this is a subject for another day.)

The result of a large cross-cultural study regarding WHR and reproductive history of females has just been announced. This study examined seven traditional societies, that is, peoples living in pre-agricultural conditions largely independent of industrialized culture. These seven societies are spread across three continents: Africa, South America, and Asia, and one island population in Indonesia. This is as “cross-cultural” as it gets.

Led by Piotr Sorokowski at the University of Wroclaw in Poland, the researchers measured the WHR of nearly 1000 women and plotted those measures against reproductive history. In their sample were women ranging in age from 13 to 95, so age had to be a control variable in their analysis. To control for overall health, they also utilized body-mass index (BMI) as a control variable and thus attempted to focus solely on fertility and WHR.

The results are dramatic. Both BMI and age separately correlated with number of children that the women had. No surprise there. However, even when age and BMI are normalized, the researchers observers a subtle, but a direct linear relationship between waist-hip ratio and number of children:

This finding turns the traditional thinking about WHR and fertility on its head. A simple interpretation of this is that greater fertility is found in women with a high WHR, the opposite of what would be expected using current theories. The graph above is the result of pooled data, but each population was considered individually and the result was consistent: number of children predicts WHR ratio weakly but significantly (p<.001 for all analyses).

This finding turns the traditional thinking about WHR and fertility on its head. A simple interpretation of this is that greater fertility is found in women with a high WHR, the opposite of what would be expected using current theories. The graph above is the result of pooled data, but each population was considered individually and the result was consistent: number of children predicts WHR ratio weakly but significantly (p<.001 for all analyses).

By focusing on traditional societies, the researchers were able to remove body weight issues brought upon by industrialization. (Obesity and type II diabetes are rare in younger people living a traditional lifestyle.) By sampling from different populations around the world, cultural effects are normalized as well. Earlier studies have attempted to discover such a connection but were confounded by modern health issues and also cultural considerations. In the industrialized world, women make informed and technology-assisted choices about their reproductive destiny that have little to do with health, attractiveness, and other variables. In addition, attractiveness is a feature that is comprised of many interconnected variables, most of them shaped by culture and other factors that are poorly understood.

The complexity of both attractiveness and reproductive choices is partially why some other studies failed to reveal a significant correlation between WHR and fertility. By focusing on traditional societies and examining several of them, this new study effectively cuts through some of the “noise” and in so doing, reveals an underlying pattern.

The surprising pattern they found provides a new twist and forces us to re-examine how attraction to WHR may have evolved. What can explain this surprising correlation?

One way to answer this is to invert the relationship. Rather than waist-hip ratio being purely predictive of future fertility, it may also be reflective of past fertility. In other words, other things being equal, a lower WHR may tell a potential mate that a female’s days of reproductive investment are ahead of her, not behind her. Yet another way to say this is that women transition from low to high WHR as they give birth to more children, a conclusion supported by this study and others.

Thus, the attractiveness of a low WHR could have evolved as a means of helping men detect and favor those with greater future reproductive potential, not just fertility in general. As Kasia Pisanski, the vocal experiment who discovered the connection between vocal features and WHR, told me, “I find [that argument] convincing, that a high WHR could indicate that a woman already has children (men don’t want to invest resources in another man’s children).”

This interpretation especially makes sense if we consider that a low WHR does indeed correlate well with potential fertility in nulliparous (childless) women.

So, rather than contradicting the prevailing thinking about why we are attracted to a low WHR, this result strengthens and extends the attractiveness theory. In general, this attraction could have been favored by evolution because a low WHR is a good indicator of the kind of hormonal balance that supports health and reproductive potential. It is also a reliable indicator that a woman has not already had a large number of children.

Wait-hip-ratio is a fascinating phenomenon for evolutionary psychology. If this physical feature truly correlates with future reproductive potential, it makes sense that we would have evolved to find it attractive. If we assume that men have a variety of tastes and there is at least some genetic component to that, those that happen to find a low WHR attractive would have been rewarded with more offspring. This attraction would then have become enriched in future generations.

Of course, this cannot be considered in isolation. A predominance of preferences in one direction can often lead to counter-selection in another direction, especially in a highly social species living in small communities. There are also confounding variables of social rank, physical health and prowess, and even hereditary social position. The many complications of the variables at hand, attractiveness, health, fertility, probably explain the weakness of the correlation. Individuals have individual tastes and desires, both for their mate and for their own future.

Nevertheless, given that a mechanistic connection in the form of hormonal balance has been found, a real biological and evolutionary phenomenon seems to be at play here. A low waist-hip ratio is caused at least in part by hormonal status that also leads to cardiovascular health and reproductive success. It only make sense that many humans find a low wait-hip ratio attractive.

-NHL

I quote from your article “A simple interpretation of this is that greater fertility is found in women with a high WHR,” which as you say is counter intuitive.

Could it be that the independent variable between waist-hip ratio and number of children is the latter? And with increasing age and with more children women (god knows why but men too) have a bigger waist and hips but perhaps the effect on the waist is more.

Incidentally the graph depicting the two variables is also shown with the number of children in the X-Axis and WHR as the Y axis (dependent variable)..

Maybe we thought that the number of children was determined by the WHR. But perhaps its the other way around. As a lady friend of mine once explained to me, one can estimate a woman’s age and number of children by only looking at her from the back (her gait, waist, hip size etc). This last point is strictly not scientific.I have included it only to show what could perhaps be the independent variable.

LikeLike

Yes, that is what I was trying to say. A low WHR correlates only with potential fertility. When a woman has children, the WHR seems to increase with each birth, according to these data. Therefore, low WHR is a signal to men of future fertility, while high WHR is a signal of low fertility (due to health) or that she already has lots of children. We need more evidence, particularly longitudinal, rather than cross-section, studies.

LikeLike

One can probably guess her age (fairly) accurately, but the number of kids? Not happening…not these days, anyway!

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff.

One of the things that seems to me that has been left out of this discussion, is post-partum mechanics. Wide hips are great for carrying kids, and so decrease strain & fatigue. That would be a separation from the other primates, who don’t share the long childhood humans have.

And so it could also be a quiet genetic attraction: men don’t know *know* why they like big hips; but men who preferred them had wives who were a bit more efficient, and hence had more stamina. Over a reproductivity of 8 children or more, that efficiency could amount to quite a survival advantage In the grinder of selection.

Many authors have assumed that wide hips accommodate the large heads of newborns. But that should affect the pelvic outlet. There is no immediate reason it would affect the iliac flare.

LikeLike

more explanation here

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/comment/1050632#comment-1050632

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/comment/1099452#comment-1099452

LikeLike

Watch a Kent Hovind seminar as you need to relearn everything if you believe in the evolution theory.

LikeLike