Happy Pride!

In honor of pride month, I am reprinting below an article I published earlier this year in a special section of Free Inquiry magazine all to do with “transgender matters.” Because it included perspectives from across the spectrum, pun intended, there is much that I disagree with, passionately in some cases. But I do give credit to editor-in-chief Ron Lindsay for soliciting a wide variety of articles, and specifically giving space for me to present my comprehensive perspective of the emerging new science of sex and gender.

This article is actually the most complete summary of the major ideas of The Sexual Evolution. Thus, if you’ve already read the book, you can skip this article. (And PLEASE go give it five stars on Amazon if you haven’t yet!)

But if you haven’t read the book yet, this article is like the Cliffs Notes, so read on!

The article appears here in its entirety, courtesy of Free Inquiry, which is published by the Council for Secular Humanism, a program of the Center for Inquiry.

And yes, the title that I chose was a troll move, designed to provoke my critics.

-NHL

<<<<

GET GENDER IDEOLOGY OUT OF BIOLOGY!

Few topics in modern political discourse are as fraught as gender. It is misunderstood, misconstrued, and misused, and opponents frequently lampoon each other’s “gender ideology.” Ideology? Really?

Gender is a psychosocial phenomenon that flows from the biology and natural history of sex. As such, the topic of gender is firmly rooted within the natural sciences, disciplines in which there should be little space for ideologies. No one speaks of the ideology of predator-prey relationships, sound perception, or gene regulation. One might even say that ideology—the a priori commitment to a belief system—is antithetical to the scientific endeavor. After all, the natural progeny of ideology are biases, which are direct impediments to knowledge.

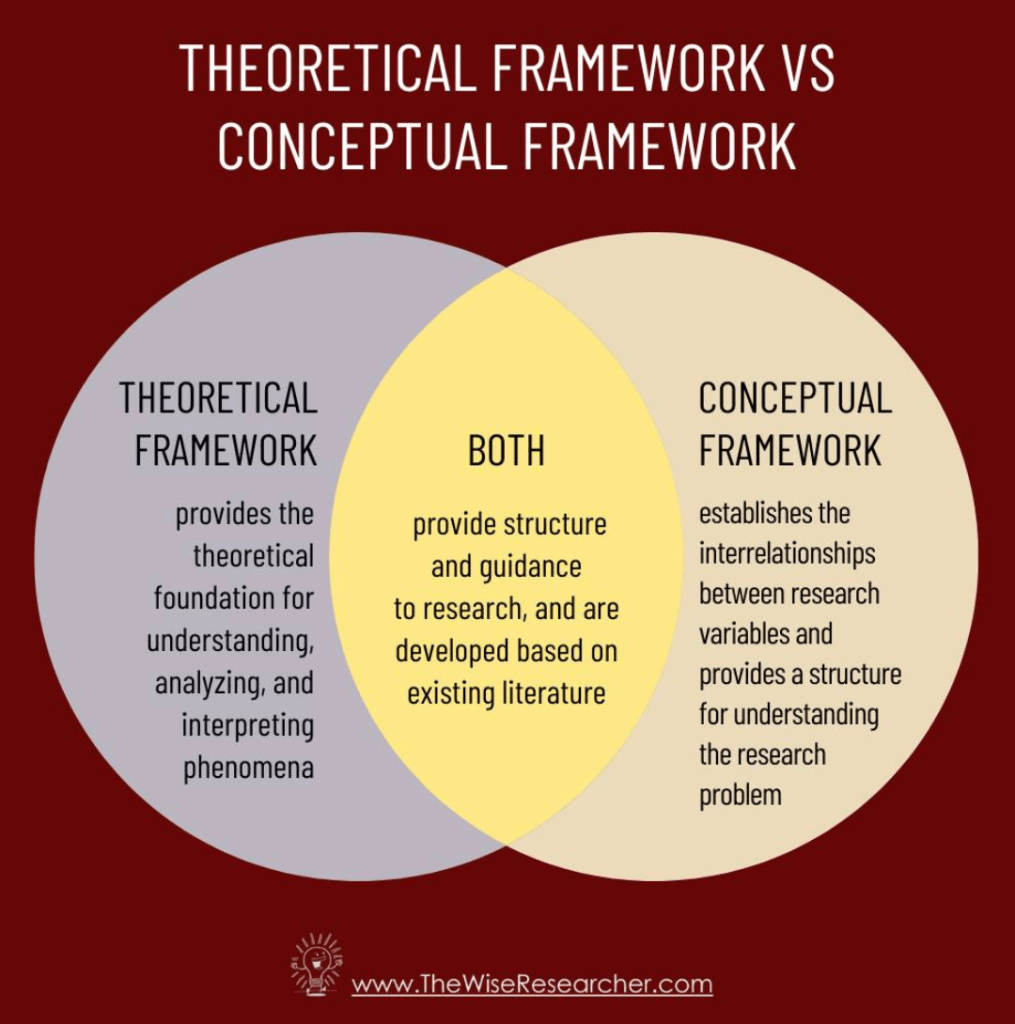

In biology and other sciences, when there are competing ideas about the nature of things—the hallmark of an active area of research—we don’t invoke ideologies. Instead, we speak of theoretical frameworks, because, to be fully understood, the evidence collected by biologists must be organized into a coherent structure. A framework doesn’t necessarily flow directly from data but rather is built from data as a means to comprehend it. If data refers only to the observable evidence, framework refers to the underlying biological reality that is often too large to see all at once.

For example, if we want to understand the social structure of a newly discovered animal species, we must collect data repeatedly, over years of time, taken from different perspectives and considering different social relationships. These data fill dozens of research articles until finally an accurate picture of the species’ social life emerges. This helps explain what we observe, and subsequent research will either further build out this framework or will challenge it and force its revision. Science doesn’t always get things right on the first try, but it is a self-correcting enterprise that homes in on the truth as our theoretical frameworks are continually updated.

Gender may be an ideology in political and policy debates, but in the field of biology, gender is a framework, a way of understanding and organizing our observations about the reproductive or sexually dimorphic behaviors of animals. While researching my new book, The Sexual Evolution: How 500 Million Years of Sex, Gender, and Mating Shape Modern Relationships, I immersed myself in the scientific literature on gendered behavior in animals. I was saddened to conclude that the gender framework in biology has, in at least some cases, been built on a faulty foundation that is littered with biases. Fortunately, even the most stubborn biases will eventually yield to evidence.

The Gender (Non)Binary

Among the faulty frameworks that are overdue for revision, the gender binary is certainly near the top of the list. Fortunately, biologists have been pecking at this one for over a century, first nibbling around the edges by admitting that there are exceptions and now taking aim at the premise itself.

What I mean by a gender binary is the notion that, when it comes to reproductive behaviors in animals, there are only two modes: male behavior and female behavior. But we have known for quite some time that, in some species, there are different kinds of males or females that pursue reproduction in markedly different ways. Importantly, this doesn’t just refer to multiple mating strategies that a given animal can choose from. Rather, in some species, there are established categories within each sex, and individuals do not, perhaps even cannot, move between them.

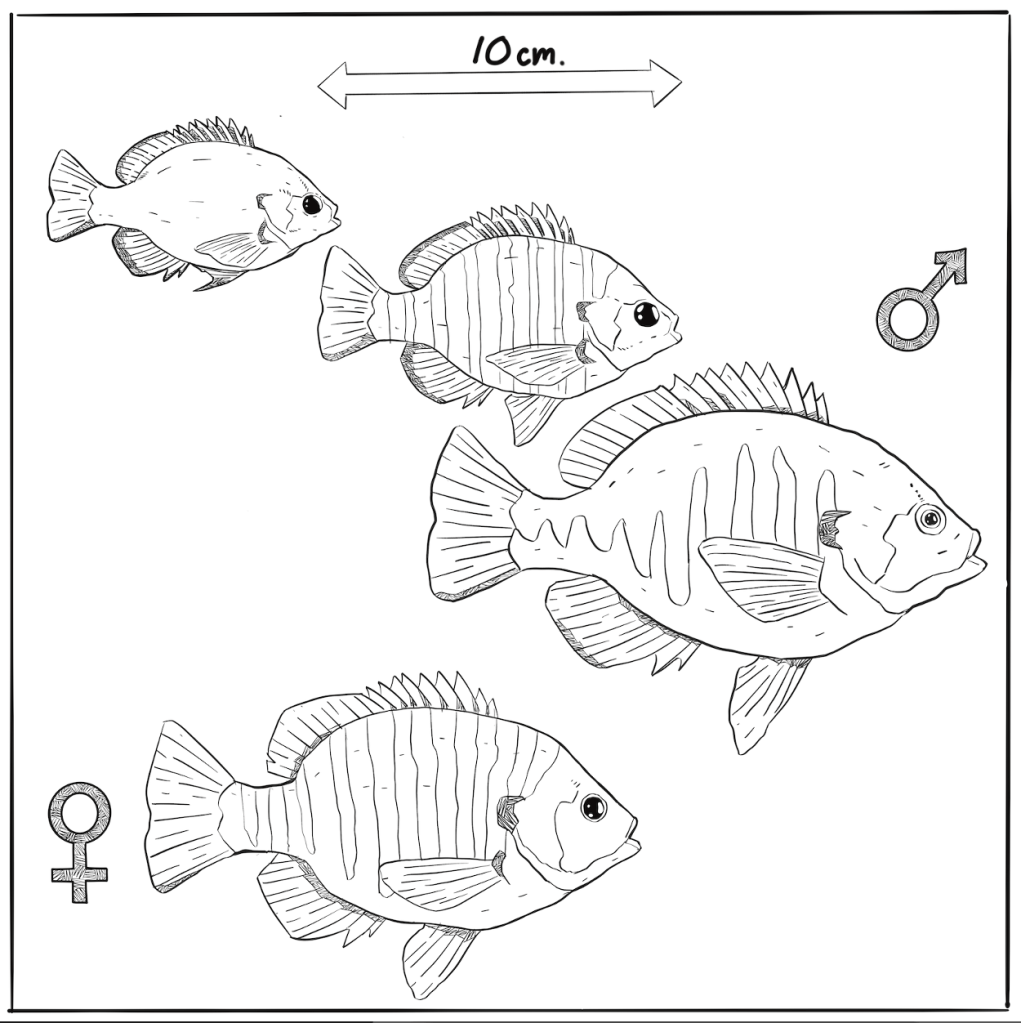

The example made famous by biologist Joan Roughgarden is the bluegill sunfish, among the most plentiful fishes in freshwater lakes and streams in North America. In these fish, there are three different kinds of males, often called small, medium, and large. The large males are dominant in many ways, including in abundance, and are the all-important nest-builders and female-attracting studs of this species. But 10 percent of the males are much smaller, never build nests, and never court females. They are called “sneakers” because they pursue paternity by attempting to dart into a nest after a female has laid eggs and achieve paternity through sheer theft.

Another 15 percent of males are medium sized and often called “cooperators” because, rather than wooing females on their own, they attempt to partner with large males and work together to entice a female to lay eggs in their jointly guarded nest. In fact, large males and cooperator males have their own distinct mode of courtship that they use prior to agreeing to the partnership. And studies have shown that, all else being equal, females prefer large males that have an attached cooperator over those that don’t, presumably because the two males are better than one at guarding a nest. (Female sunfish quickly depart after depositing eggs, leaving males to guard them until they hatch.)

Importantly, sunfish cannot simply move among these categories. While it was previously thought that the small and medium males were simply juveniles, we now know this is not the case. Although sneakers do mature into cooperators if they live long enough, neither becomes the large males, which must survive for seven long years before becoming sexually mature. Thus, bluegill sunfish have three genders of males. Insisting on a simple binary obscures gender diversity in these fish and misses the reality of their reproductive lives.

Sunfish do not stand alone. Sneaker males have been recognized in many species for centuries, but biologists largely dismissed them as runts. Cooperator-type males have also been noted in species from lions to ruffs, but, as with sneakers, these were long assumed to simply be suboptimal males, frustrated by their submissive position. Increasingly, biologists are noticing that minority forms—both male and female—are a stable and reproductively successful segment of the population. Because these forms persist and reproduce, they cannot just be dismissed.

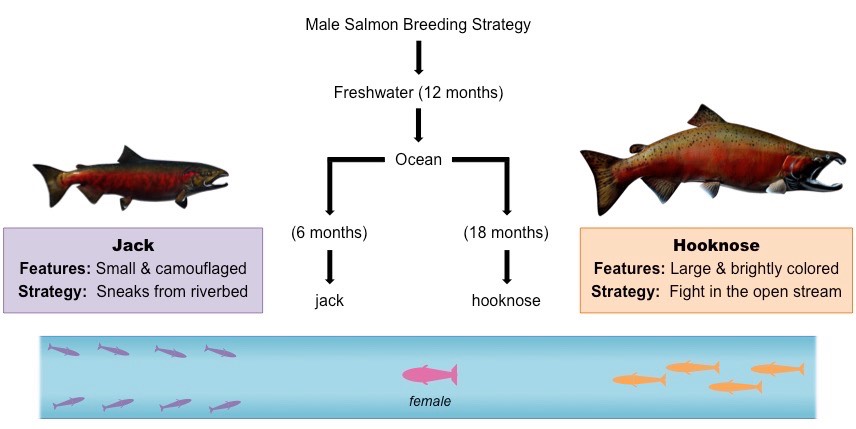

It turns out gender variation is a good long-term strategy. For example, both Atlantic and Pacific species of salmon, which are in different genera and thus not close relatives, have two forms of males—jacks and hooknoses—that vary by size and lifespan. Hooknoses spend more time in the open ocean, while jacks migrate more quickly back into the freshwater for spawning (and death).

Having two kinds of males means that the species can easily switch back and forth between spending more or less time at sea, which could come in handy if and when environmental conditions change. Of course, nature is always generating further variation on established traits, and so salmon have a built-in means of adapting their lifestyle if need be. There is nothing wrong with variants that don’t quite fit the expected mold. In fact, variants are the raw material for future adaptation. That’s how natural selection works.

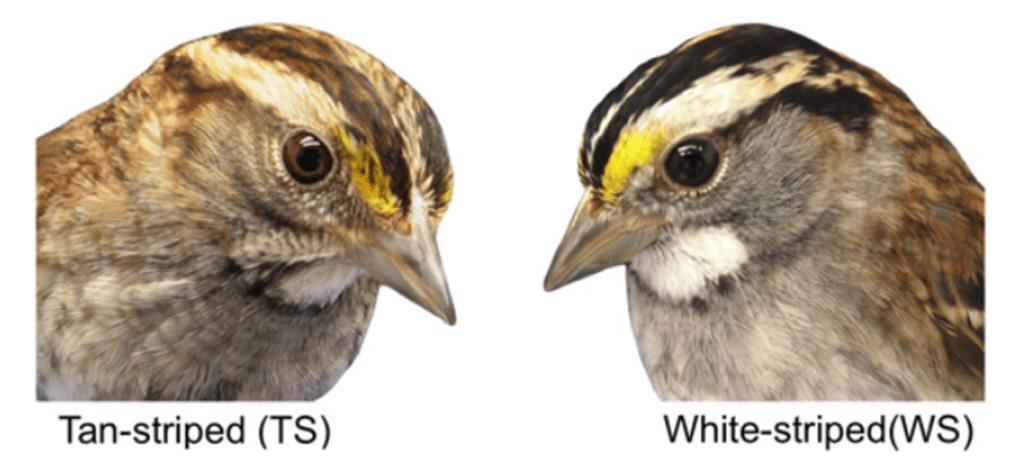

White-throated sparrows have gone further and de-coupled sex and gender altogether. There are white-striped morphs, which are larger, more territorial, and more musical, and there are tan-striped morphs, which are more devoted and protective parents. While gender bias once led us to conclude that those are masculine and feminine forms, it turns out that males can be either morph and so can females. But mating pairs always consist of one white-striped morph and one tan-striped morph, regardless of sex (and yes, many pairings are same-sex, more on that below).

In sparrows, an aggressive territory-defender and a doting parent make a successful couple. Assigning those two forms to two separate sexes is one way to do things, but sparrows have gone a different way. Nature is endlessly creative, including with gendered behaviors.

Female Mimicry

Gender ideology has been so pervasive and so dominant that it hung like a storm cloud over mountains of otherwise careful research. A framework called female mimicry has been constructed to explain why some males don’t behave in expected ways. If we are committed to a strict gender binary, when a male behaves outside male-typical modes, the only other mode available is female-typical. But gender diversity is a simpler way to understand that, and isn’t the simpler explanation usually preferred?

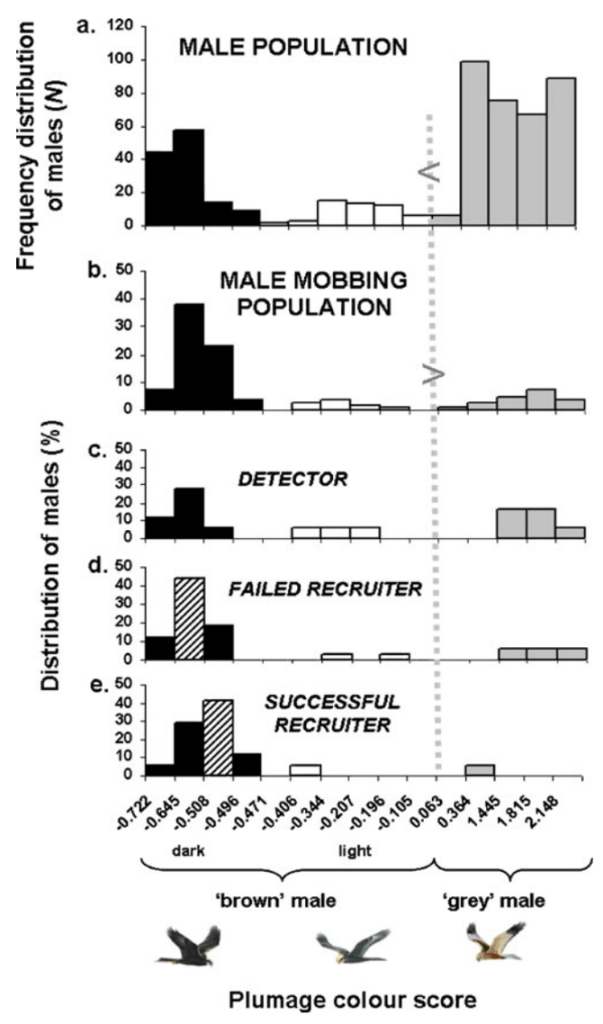

For example, in western marsh harriers, a large bird of prey native to Africa and Eurasia, most males are highly territorial, staking out a prized plot of land that they use to attract a female mate, aggressively defending it from encroachment by other males. However, it was recently discovered that a minority of males are different. They neither defend a territory nor fight with other males, and they move around freely, unbothered by the territorial males even as they seek and obtain copulations with the females.

Many biologists believe they manage this by tricking other males into thinking they are females. You see, most males have only gray-brown feathers on their head, while females have conspicuous white feathers on top. The female mimics also have these white feathers, which helps them avoid attacks from other males.

But let’s take a closer look. The white feathers are pretty much the only female-typical characteristic these supposed female mimics have. They are the same size as the other males, which is about 30 percent smaller than the females, on average. (That’s twice the average size difference between human men and women.) They also have the same striking yellow eyes that other males have. If these are female impersonators, they are the worst drag queens ever. And keep in mind that birds of prey have the most highly developed visual system in the entire animal kingdom. Their visual acuity at a distance is about five times more powerful than ours. And yet, a few white feathers are enough to fool them?

Perhaps instead, the white feathers are not deceptive but rather are used as a flag of peace that advertises they have no wish to challenge any territorial claims. It’s a borrowed signal that pacifies the other males. It says, “I’m not challenging you.” But why do the other males tolerate the presence of these interlopers? Well, it turns out that these males also engage in a behavior that is female-typical: mobbing.

Mobbing is a highly coordinated practice for chasing out egg predators such as wolves, foxes, badgers, small rodents, and even other birds. When a female—or a white-feathered “female mimic”—spots a would-be egg predator, they sound an alarm call and nearby birds band together to neutralize the threat. The main males, however, do not participate in this behavior, probably because they are just too antisocial for that. They simply cannot tolerate the presence of another male within a few hundred meters—unless, that is, the male sports the white feathers, because those males will not challenge them for territory and are helpful for rooting out the egg predators. In fact, biologists have claimed that the mobbing behavior is part of their female mimicry.

But maybe this is just another male gender. Rather than trying to fight it out with the other males, these guys have found another way. Instead of cooperating with other males like in sunfish, they cooperate with the females. Because the dominant males are polygynous and usually attract two or even three female mates, there are a lot of unpaired males around. These minority males have found a way—through natural selection—to evade territorial aggression while contributing to something useful. And they are rewarded for their trouble with a respectable measure of paternity. This is more than just an alternative mating strategy; it’s a heritable and stable biological difference. Apparently, the social structure of harriers includes two types of males, both of which are important.

Another piece of evidence that this is another male gender is that we’re not talking about a few outliers. These so-called female mimics compose 40 percent of marsh harrier males. It is common sense that, in general, camouflage can work for an individual here and there but not for large droves of them. Oh, and one more thing: if the territorial males are really fooled by the mobbing males, why don’t they try to mate with them?

This is not to say that I am skeptical of all such claims of female mimicry in animals. I even discuss some of them in my book, such as the female-mimicking garter snakes that trick other males into sex to steal their body heat and tire them out. But in animals with larger brains and more sophisticated sensory systems, gender diversity and borrowed signals seem like a much more plausible framework than female mimicry, at least in some cases. And because this framework is still in its infancy, who knows how common gender diversity really is in animals.

Let’s Talk about Sex, Baby

The issue of biological sex may be even more fraught than gender! Even as our society has slowly come around to the understanding that sex and gender aren’t the same thing, confusion, disagreement, and conflict have multiplied. At the risk of oversimplifying the matter, gender is largely a matter of inward identity and outward expression, while sex is a physical property of an animal body and applies to plants, some fungi, and protists. If gender is about behaviors and feelings, sex is about cells and organs. For the most part, those definitions work just fine.

Diversity in gendered behaviors is one thing, but diversity in the sexes of animal bodies is quite another. And yet, in my book, I devote a whole chapter to the diverse ways that animal bodies can be sexed. On the surface, this seems a simple matter. If a body makes sperm, it is a male; if it makes eggs, it is a female. If only sex were always that simple!

At the outset, we must remember that many animal species include hermaphrodites—bodies that can make both sperm and egg—either alongside the single sexes or instead of them. So at the very least, there are three sexes of animals to consider. Some retain the ability to make both sperm and egg through their entire life cycle, called simultaneous hermaphrodites, and some can switch from one sex to the other, called sequential hermaphrodites. Among the sex switchers, some always switch from one sex to the other as part of their usual developmental pattern, and some do so in response to specific environmental conditions. While most can only switch once, a few very strange species can go back and forth apparently without limits.

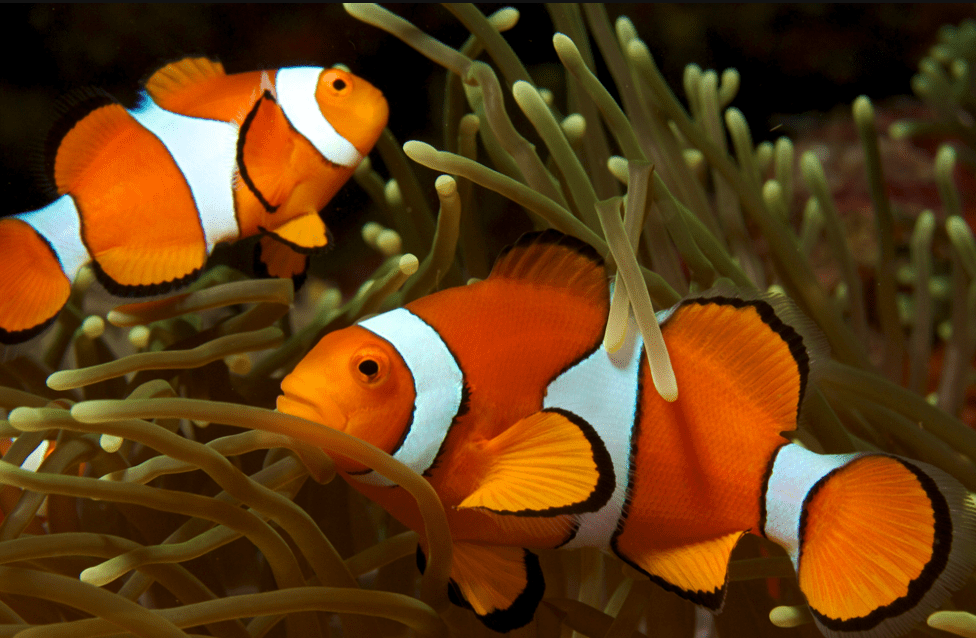

Some animals even switch their sex based on social conditions. For example, in a clownfish group, the oldest and largest fish is the alpha female, and she is the only female in the group. She only mates with the next oldest and largest fish, the alpha male. When the alpha female dies or is lost, the alpha male switches his sex and becomes the alpha female. The beta male then becomes the alpha, and all the younger fish move up in rank, awaiting their turn to become the alpha male and then the alpha female. Most, of course, don’t make it. In fact, the restriction of breeding privileges to the oldest two fish in the group is a form of quality control. Clownfish self-impose their own unique form of natural selection by ensuring that only those that survive a long time are allowed to breed.

Hermaphroditism is common among animals. Outside of insects, around one-third of animal species include hermaphrodites in their number. While we used to think of this as a purely invertebrate phenomenon, a throwback to simpler times, it has now been discovered in a wide variety of fish and amphibians, and the diverse ways in which it works is dizzying.

But, you may ask, if the sex of an animal is determined by its chromosomes at the moment of conception, how can it possibly be changed later on? Well, it turns out, chromosomes are not the only way that sex is determined in animals. In some, sex is determined by the time of year they hatch. In others, population density determines sex. There are some parasites that can control the sex of their host. And temperature is among the most common factors in the sex determination of reptiles, leading to a recent headline declaring that “climate change is turning female bearded dragons into males.”

Even among chromosome-determined species, there is a wide variety of systems. There is the ZZ/ZW system of birds and some reptiles and the ZZ/ZO system of some insects. In the social insects, males have only one copy of their genome, while females have two full copies. Even in the familiar XY system used by mammals and some insects, there are variations, with some being Y-determined and others being X-determined. The platypus, ever the oddball among mammals, has ten sex chromosomes, with females being XXXXXXXXXX and males being XYXYXYXYXY. Madness!

Hermaphroditic animals frustrate our preference for a simple binary when it comes to sex, but there are species at the other extreme as well. Parthenogenesis is the process of an organism developing from an unfertilized egg. While this is common in social insects, it was previously unheard of in vertebrates. Once again, nature is full of surprises. From a virgin birth to a female hammerhead shark in Nebraska, to a solitary Komodo dragon hatching an egg in the United Kingdom, scientists are observing parthenogenesis in an increasing number of vertebrate species. These are often—but not always—a product of isolated zoo animals, and that may hold the key to this intriguing phenomenon. When it comes to propagating one’s genes, desperate times call for desperate measures.

There are even some animal species that have opted purely for parthenogenesis and have done away with males altogether. Among them are fish, amphibians, and more than eighty species of reptiles, in addition to innumerable invertebrates. The bdelloid rotifers are similarly all-female but reproduce through simple cloning, achieving genetic diversity by an entirely novel mechanism: by “ingesting” new genes from their environment!

The point here is that throughout the animal kingdom, there is considerable diversity and even flexibility when it comes to how, when, and why an animal becomes male or female, and there are more exceptions than there are hard rules. Biology loves exceptions, because creativity and diversity is one of the central themes of life.

The Strangest Animal of Them All

By now you may be incredulous as to how any of the sexual diversity described above applies to humans. After all, there are no true hermaphrodites among us, and we have not managed parthenogenesis or human cloning. At least not yet. But human bodies do exhibit a striking degree of sexual diversity that goes far beyond the simple binary of our gametes.

There are sexually dimorphic differences throughout the human body, from the obvious things such as height, body hair, face shape, upper body strength, breast size, and waist-to-hip ratio to more subtle things such as basal metabolic rate and blood cell counts (males have more red cells, females more white ones). And these translate into important differences in conditions of health and disease. Women are nine times more likely to develop lupus, while men more often suffer heart attacks. Women are more likely to be depressed, but men are more likely to die by suicide. These differences have nothing to do with our gametes. Sex is something that affects our entire bodies, not just our gonads.

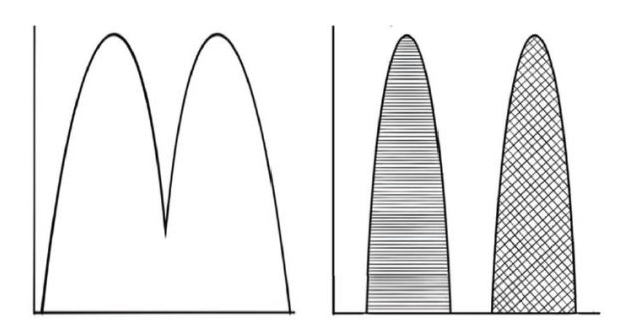

Moreover, the myriad sexual dimorphisms we see throughout our bodies always exist on a spectrum. The sex differences are bimodal, not binary, and there are plenty of us who fall outside the sex-typical expectations on one or more measures. There are women who can grow beards and men who can produce milk. We all know men with “child-bearing hips” and women who can arm-wrestle with men, and there is no reason to think they are unhealthy or infertile.

Even the few sex differences we see in the brain—things such as ratio of white to gray matter and the size and shape of the corpus collosum, hippocampus, and amygdala—are so messily bimodal (not to mention equivocal across studies) that when we consider the brain as a whole, most people will fall outside of their sex-typical range on at least one measure, sometimes more. We are all mosaics of these bimodally dimorphic traits. Biology just doesn’t often traffic in binaries.

Even genital anatomy—which seems to be what most people obsess over—can display more gray area than is usually discussed in polite company. While only 0.02 percent of babies are born with truly ambiguous anatomy, that drastically undercounts the true variation by only considering the lowest part of the bimodal curve. There is a great deal of anatomical diversity out there, giving rise to a vibrant intersex community of affirmation and solidarity, most of whom do not seek surgical intervention to make their bodies more palatable to others.

Even something as seemingly basic as chromosomal sex is not always so simple. Klinefelter males (XXY) and Turner females (XO) represent around 0.1 percent of the population. Even more common are the reciprocal conditions of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, in which an XX individual produces masculinizing levels of testosterone, and androgen insensitivity syndrome, in which an XY individual is feminized for failure to respond to testosterone, both of which exist on a wide spectrum of severity.

This is why many are calling for a continuous spectrum – a bimodal, rather than a binary, understanding of sex. While the people truly in the middle may be a small minority, they are not freaks. They are our fellow humans, and this is where I am happy to embrace the ideology that all humans are worthy of dignity and respect. Further still, insisting on a sex binary also ignores the many bimodal dimorphisms throughout the body and instead centers the ovaries and testes as the sole determinants of sex. But our entire body is sexed, and all those other dimorphic traits have far more bearing on our daily lives than do our sperm and egg cells. For those who want to focus only on those, there is already an appropriate term—gametic sex—that is almost perfectly binary. In the rest of the human body, bimodal distributions are what we see.

Sexual Congress

As interesting as gender and biological sex are, the real fun of sex is, well, having it. And that’s really what most of my book is about. For centuries, the matter of when, how, and with whom we should have sex was dictated by religious and cultural norms rather than biology, but a simple look around the animal kingdom reveals that the human approach to sex is quite unusual.

Long were we told, including by biologists, that the primary purpose of sexual intercourse in animals is to produce offspring. This was almost certainly due to projected anthropomorphism. Because humans were only supposed to have sex within the confines of a permanent, consecrated, heterosexual coupling, those intrepid Victorian naturalists squinted hard to see animals that way as well. Their Christian ideology colored their vision.

But we now know that animals have sex for a whole host of reasons. They use sex deceptively, competitively, and transactionally. They use it for bonding between mated pairs, as well as social cohesion within a cooperative group. An animal can pursue sex to climb the social ladder, either by domination or affiliation. And they even have sex for the reason we most often do—just for the fun of it. Animals even masturbate, and there are good biological benefits for their doing so.

Yes, animals have sex for pleasure, and why wouldn’t they? The dopamine-fired reward center in our brain, which is copiously tickled by sexual activity, is hardly a uniquely human phenomenon. While religious ideologies often view pleasure as a path to damnation, biology recognizes that pleasure is a powerful means to drive important behaviors.

The extensive utility of sex in the social life of animals begs the question of why this behavior should only be directed at members of the opposite sex. To have an aversion to sex with half of your conspecifics would seem to bring only costs for social animals. Indeed, this is exactly what we see. Same-sex sexual activity is rampant in social animals but largely absent in solitary ones, additional evidence for the many social purposes of sex.

Seeing how freely other animals have sex with each other really makes you wonder how all that sexual promiscuity was missed by biologists for so long. The answer, of course, is bias. Previously, anything resembling sex between two animals of the same sex was either ignored as aberrant or mistaken, or explained away as mere dominance struggles. While pursuing dominance could indeed be a legitimate explanation for some same-sex sexual activity (but nowhere near most of it), that doesn’t mean it isn’t sex. Sex is sex, regardless of the intended goal. The sex-is-for-procreation ideology prevented biologists from seeing its many expansive purposes.

And speaking of promiscuity, sexual dogma also led scientists to completely misunderstand what monogamy is all about in animals that pair-bond. Because most mammals are promiscuous and eschew pair-bonding altogether, birds bore the brunt of this particular misconception. Migratory birds in particular are prolific pair-bonders, with more than 90 percent forming socially exclusive pair-bonds that last at least a breeding season. Half of those mate for life. This delighted nineteenth- and twentieth-century Western scientists who were all too eager to celebrate this model of the ultimate human ideal: lifelong monogamous marriage.

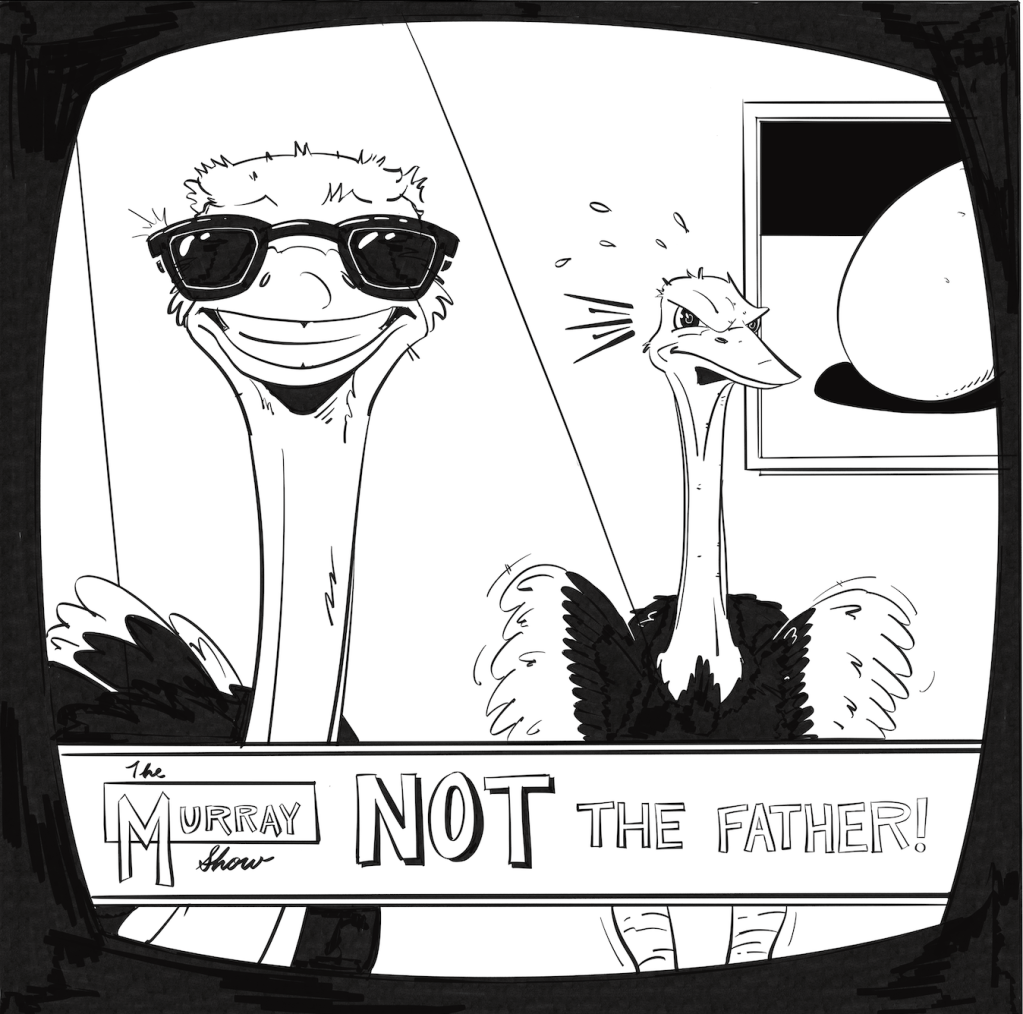

Blinded by their bias, scientists had no idea that pair-bonding in birds is socially monogamous but not sexually exclusive. Only with the advent of DNA-based paternity testing were scientists forced to admit that pair-bonded birds do plenty of sleeping around. Beginning in 1987, ornithologists began subjecting their favorite bird species to genetic scrutiny, and, one by one, the answer kept coming back like an episode of the Maury Povich Show: “You are not the father!”

Copyright Nathan H. Lents, The Sexual Evolution. Original artwork by Don Ganley

The term extra-pair paternity was quickly applied, as though these were exceptional cases that broke the rules. We now know that, when you factor in brood parasitism (the practice of birds sneaking their eggs into other birds’ nests), in most species, it’s quite usual that bird nests include at least one egg that is not the progeny of one or both birds that care for it.

In mammals, sexual monogamy is nearly unheard of, even among the most doting mates. In some species, this causes jealousy and conflict, but in many more, they just don’t seem to care. The point here is that, for centuries, biologists were completely wrong about the sexual aspects of pair-bonding in birds and mammals. Ideology can powerfully overwhelm otherwise careful research.

The misunderstanding of what monogamy is, and is not, is yet another reason that same-sex sexuality was completely overlooked. Most seabirds, for example, are not sexually dimorphic, and even expert birders cannot distinguish males from females—even upon physical inspection. So when birds such as albatrosses were seen pairing up, there was no reason to think that the pairs were anything other than heterosexual. Once again, this was completely wrong. Biologists have now observed same-sex pair-bonding in pretty much every species in which they have looked for it. In birds, mammals, and beyond, same-sex sexuality is everywhere.

Whether we’re talking about an isolated act or lifelong pair-bonding, there can be clear benefits to an animal to pursue sex with any member of their species, not just those of the opposite sex. In fact, to eschew sexual activity with half the population could bring only missed opportunities and nothing gained. While this doesn’t quite mean that there is no such thing as sexual orientation, it does mean that, if the human sex drive is anything like what is observed in other animals—and why wouldn’t it be?—we should probably be thinking about it in less categorical ways. The notion that sexuality is vague, flexible, and responsive to the social environment is not so outrageous when you consider that’s how it seems to work in other species, including and especially our closest relatives.

Conclusion

One of the most enduring themes in the field of biology is that living things are constantly generating diversity as an evolutionary investment for an uncertain future. I find it gratifying that we are finally beginning to appreciate the diverse way that social animals, including us, approach gender and sexual relationships. To truly do that, we must keep ideology out of biology.

You can read more detail about all of this, and more, in my book, The Sexual Evolution.

-NHL

Leave a comment