[This post is a collaboration with Soraya Alli, a student at the Macaulay Honors College at John Jay College.]

An animal’s sense of smell (olfaction) plays a major role in mother-offspring recognition in colony-living species. This includes bats, goats and sheep, pigs, dogs, and many others. Even human mothers can identify their own children by smell!

On the other hand, there is not much information on mother-offspring olfactory recognition in solitary-living species, whose adults spend a majority of their lives without others of their species. The domestic cat, for instance, is considered a solitary species. Because they don’t associate with others, cat mothers will rarely find themselves in a situation where they must discriminate between own and alien kittens.

“Chemical cues” are assumed to play an important role in cats’ daily life and in the development of the mother-offspring relationship. Cats have a variety of scent glands distributed over their body (cheeks, abdomen, paws, above the tail and near the anus), and with these they frequently mark objects in their surroundings. During encounters, cats routinely sniff each other’s faces and each other’s anogenital area. Cat mothers also sniff and lick their kittens upon entering the nest, focusing on their anogenital area.

Nevertheless, a study was performed by Ohkawa and Hidaka (1987) on domestic cats and it reported that mothers of this species do not have the ability to differentiate their own kittens from alien ones. Researchers in Mexico City recently decided to revisit this question. As they wrote in their article, “From an evolutionary perspective, it could be interesting to investigate whether this failure is a result of domestication or a general characteristic shared with the domestic cat’s presumed wild ancestors, F. silvestris lybica [African Wildcat] and F. silvestris silvestris [European Wildcat].”

Cats, Kittens, and Lots of Sniffing: “Are You My Child?”

For their study, Bánszegi, et al examined two aspects of maternal discrimination in the domestic cat: (1) whether cat mothers can distinguish between their own and alien kittens, and (2) whether cat mothers use olfactory cues in the discrimination process. The study consisted of three experiments: (1) retrieval tests, (2) anogenital inspection, and (3) general body odor.

A total of 19 domestic cat mothers (12 mix breed, 4 Persian, 2 Bengal, 1 British short hair, ranging from ages 1 to 4 years) who had recently given birth to their litters in private homes in Mexico City participated in this study.

Experiment 1: Retrieval Tests

For each cat mother, one experimenter placed, in alternating order, 2 alien and 2 own kittens approximately 1 meter from the entrance of the cat’s nest in separated plastic containers, leaving 25 cm between kittens.

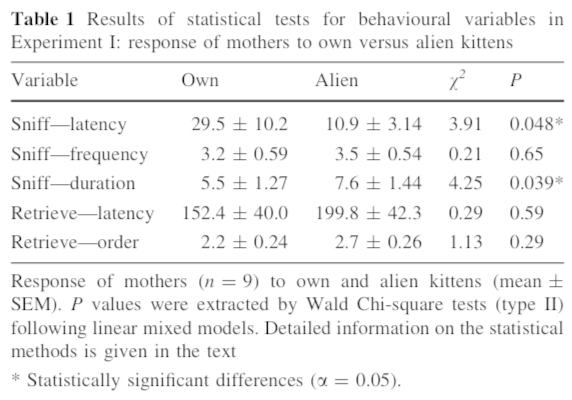

The experimenters measured the latency, frequency and duration of the mothers identifying (i.e. sniffing) each kitten and the latency and order of retrieving kittens into the nest. The experimenters found the mean latency to sniff the first kitten: 1.58s ± 0.26s, mean latency to sniff all kittens: 20.2s ± 5.4s, mean duration of sniffing: 6.53s ± 0.95s , and mean frequency of sniffing a kitten: 3.36 ± 0.40.

More importantly, there was little difference in mothers’ behavior toward own and alien kittens — the only difference being that mothers tended to sniff alien kittens earlier and longer. Furthermore, the researchers concluded that “the slight, yet significant differences” in the latency and duration of the first examination of the two types of kittens suggest that mothers noticed there were unfamiliar kittens present, inclining them to investigate those first.

When it came to retrieving the kittens, 7 of the 12 mothers retrieved all 4 kittens, 2 retrieved only 2 kittens (in both cases 1 own and 1 alien kitten), and the other 3 mothers did not retrieve any. The researchers found no significant difference in the latency to retrieve own versus alien kittens, nor in the order of retrieving them. The researchers also pointed out that these results are consistent with the study done by Ohkawa and Hidaka (1987), which found that cat mothers do not discriminate between own and alien offspring; in fact, they retrieve them equally.

Experiment 2: Anogenital Inspection

In a second experiment, the researchers were interested in knowing whether cat mothers are able to discriminate between own and alien offspring, and if so, “whether they use olfactory cues to do so.” For this, the researchers used something called the olfactory habituation-discrimination technique. Habituation is the diminishing of a physiological or emotional response to a frequently repeated stimulus, which in this study was scent.

The experimenters presented 3 different kittens from each mother’s own litter (habituation trials), followed by the introduction of a non-kin kitten. The kittens were presented individually, wrapped in clean unscented cloth with only their anogenital region exposed, which the mothers were only allowed to sniff.

Mothers spent very little time sniffing their own kittens’ anogenital region, but spent a significantly longer time sniffing that of the non-offspring kitten. These results highlight that cat mothers can differentiate between their own and alien kittens even though the kittens were silent to the human ear (unlike in experiment 1). The researchers concluded that the alien kitten’s scent was distinct from that of the mothers’ own kittens.

However, since the experimenters could not rule out the possibility of the mothers using cues other than smell to discriminate between own and alien kittens, they conducted a third and final experiment where they presented mothers only with kitten olfactory cues.

Experiment 3: General Body Odor

For this final experiment, each kitten was rubbed with a dry, sterile cotton swab stick 5 times on its back, stomach, axilla, anogenital area and on both sides of the face. The swab was then sealed and used within 10 minutes in order to preserve its scent. The experimenter individually presented the first three swabs that had been rubbed on the mother’s own kittens, followed by a swab that had been rubbed on an alien kitten, and allowed the mother to sniff each one.

The researchers found that the mothers spent a significantly longer time sniffing the swab that was rubbed on an alien kitten, in comparison to the swab rubbed on their own. The results of this experiment confirmed that cat mothers are able to distinguish own from alien young using only olfactory cues.

Conclusion

Experiment 1 illustrated that cat mothers did not differentiate between own and alien young when retrieving them. However, this did not necessarily mean that cat mothers can’t distinguish between own and alien kittens (Experiment 2), or that they may use olfactory cues to do so (Experiment 3). These findings are consistent with previous studies (1983, 2002, 2006, 2008) performed on other mammalian species where mothers did not discriminate between own and alien offspring when providing maternal care, but did discriminate when presented only with odors of the young.

In a 2007 study, Holmes and Mateo stated “if a mammalian mother nurses and cares for her own and alien young in the same manner, this should not be immediately interpreted as an inability to discriminate between them.” Furthermore, maternal care should not be the only measure of maternal recognition or discrimination of offspring.

What this study shows is that cats can tell which kittens are their own, using smell, but they don’t necessarily favor their own kittens over others. While this may seem discordant with traditional views of natural selection and nepotism, it really should come as no surprise that animals, like humans, can be kind and caring toward non-kin, especially when there is no direct threat or limited resources to distribute. As long as caring for non-kin kittens is not a zero-sum game with caring for own-kittens, what’s the evolutionary penalty?

Scientifically speaking, this study resolves the apparent contradictions in earlier studies that had come to different conclusions regarding whether solitary animals can distinguish their own offsprings from non-kin using smell. In the case of cats, they can, they just don’t necessarily care which are their kittens and which are not.

-This post was written by Soraya Alli and lightly edited by NHL.