I had the distinct honor of reviewing Richard Dawkins’ new book, The Genetic Book of the Dead: A Darwinian Reverie for Free Inquiry magazine.

Although Dawkins and I disagree on matters of sex and gender (I still have hope that he will come around a little), and I have sharply disagreed with some of his public work outside of biology, his scientific accomplishments have had enormous impacts on me at multiple stages of my life and remain hugely influential in our field of evolutionary biology.

The Selfish Gene is an unmatched classic for very good reason. The Ancestor’s Tale and The Blind Watchmaker served as direct inspiration for my own book, Human Errors. Indeed, I consider it the highest possible compliment when Errors is compared to them.

And so, the opportunity to provide my analysis of one of his books seemed like a daunting and humbling task, but a challenge that I could not pass up. I was prepared to take issue with anything I felt was unsupported, outdated, or overly simplistic and categorical, particularly in the area of sex and gender. Fortunately for me, I found nothing to quibble with. (And he praised Human Errors !)

The Genetic Book of the Dead is not only a love letter to evolution’s dazzling creativity from one of the most famous nature lovers of all time, it is also a triumph of elegant prose. In his usual style, there are witty turns-of-phrase and delicious metaphor on every page. With obvious glee, Dawkins takes us through a wide variety of interesting examples of some of life’s major themes.

Knowing that Dawkins would likely read it, I worked hard on this review, and, if you’ll permit a boast, I am really happy with how it turned out. In my opinion, this among the best pop-press articles I’ve written. And Dawkins agrees!

Without further ado, here is my complete review, published with permission, courtesy of Ronald Lindsay (EIC of Free Inquiry) and its publisher, the Center for Inquiry.

<<<<

The Dead Speak!

A Review of The Genetic Book of the Dead

Nathan H. Lents

One of the things I love most about Richard Dawkins’s books is that I am guaranteed to learn a heap of new things—even on subjects I already know a lot about. The Genetic Book of the Dead: A Darwinian Reverie is no exception. It is a lovely and far-reaching tour through life’s diversity, complexity, and variety. Perhaps paradoxically, the more we explore that variety, the more commonality we discover.

All living things have more in common than in contrast, from the mundanity of cellular metabolism to the brilliance of natural selection. The Genetic Book of the Dead reminds us that everything has a past, a deep past in fact, and that the whispers of that past can still be heard in the bodies, molecules, and behaviors we see in the present.

In a sensible world, there would be nothing controversial in this. But as we all know, nonsense abounds in our modern world. As one who, like Dawkins, too often tussles with creationists, I found myself wondering, page after page, what piffle creationists would invent to explain away each example Dawkins describes. But please do not do that. It serves only to distract from the otherwise beautiful Dawkinsian prose.

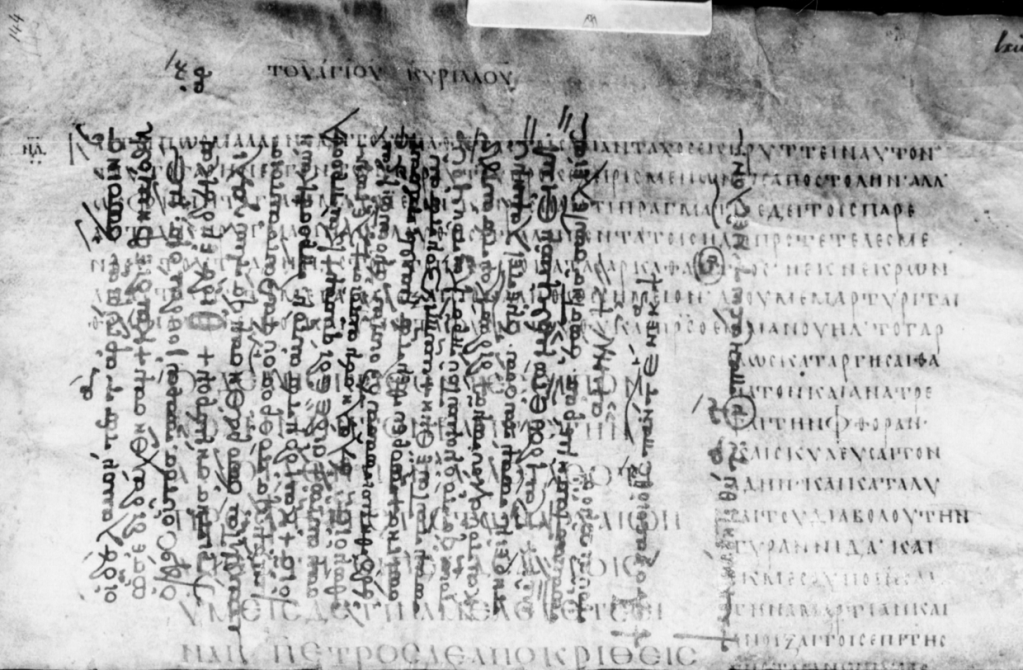

The analogy Dawkins employs throughout the book is that of the palimpsest, an ancient manuscript written on animal-skin parchment that is later erased and inscribed anew. The underlayer, having left an impression on the parchment or having been incompletely erased, can be recovered through modern methods. Famous examples include letters written by St. Jerome atop even more ancient Roman law texts; the Jerusalem palimpsest written atop plays by Euripides; and one of the earliest known fragments of the Qur’an, which was rescued from a palimpsest. As priceless as they are rare, recovered palimpsests have yielded some of the earliest unmodified versions of many ancient source texts. The palimpsests inside of us are no less precious.

The image of the palimpsest evokes the idea of a long-gone deep past, but so does the book’s title, which was intentionally and cleverly chosen. We tend to think of our genes and our bodies as doing their work for us and of evolution having shaped us for our environment, but as Dawkins repeatedly reminds us, our myriad adaptations speak of the selective environment of our ancestors, not necessarily of our own. A leafy sea dragon looks like kelp because its ancestors escaped their predators when they did, and so on. This system serves us well when we live much as our ancestors did but breaks down when environments change. This leads to evolutionary mismatch, a frequent cause of seemingly bad design in the human body.

As a staunch adaptationist, Dawkins reminds us that everything about an animal’s body traces back to selective forces that played out in our ancestors. Despite Dawkins’s famous gene-centric view, the book is not very molecular in its coverage. Instead, it is a book about phenotypes and how evolution has shaped those phenotypes through their interaction with the environment. As such, it’s more mechanistic than it seems, but casual readers will not be put off; Dawkins does not rely on jargon for his erudition. A few examples will illustrate.

In chapter three, we go on a journey from the ocean to land, back to the ocean, and back to land again—and perhaps back and forth yet again—all on the back of a tortoise! The animal body plan is like a chassis that gets tweaked and modified as animals adapt to their environments. But each round of adaptation leaves marks behind that future adaptations cannot fully reverse.

Here again, the analogy of the palimpsest is apt. All vertebrates are descended from fish, and the marks of our piscine ancestors can be found throughout our bodies, from our gill-like larynges to our water-filled eyeballs. But, as Dawkins carefully reminds us, most fish today are ray-finned and sleek, while our chunky ancestors had lobed fins. Those lobes aren’t so great for swimming but are muscular enough to defy the crushing gravity of dry land, and voila, the tetrapods limped awkwardly into the future.

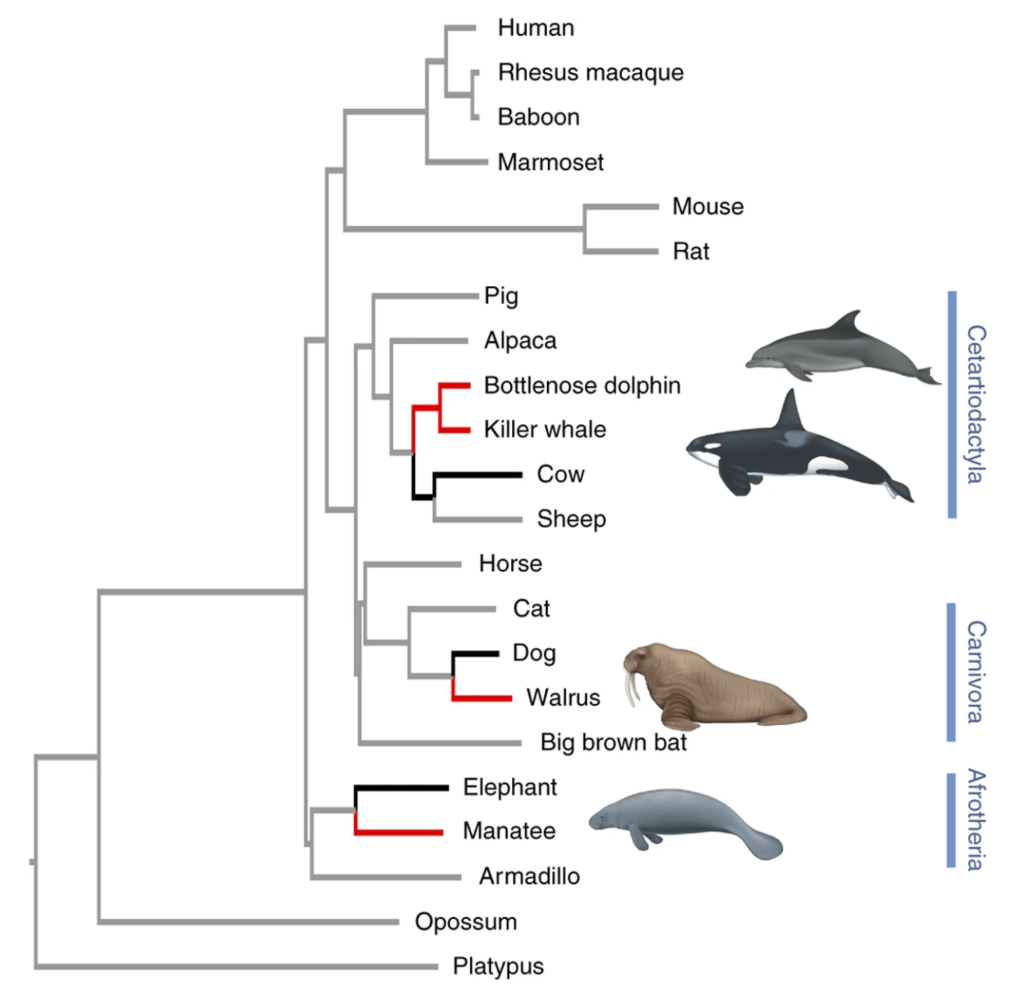

With no respect for their intrepid forebears, some tetrapods turned right around and plunged back into the depths, but the marks of their terrestrial past are abundant, some more obvious than others. From blowhole nostrils to the remnants of a pelvis, there is little doubt that cetaceans are, in a sense, telluric animals. But it was the unique insight from DNA sequences that revealed that the closest relatives to whales and dolphins are, in fact, the Hippopotamidae, not any other group of marine mammals despite the striking but superficial similarities.

And those other groups—the sirenians, the pinnipeds, and the fessipeds—all have close terrestrial relatives as well. The similarities among these groups are as interesting and informative as their differences, because each of these fully aquatic mammals solved the challenges of life at sea with a body made for land differently. Dawkins uses these and other examples to explain the power of convergent evolution. History may not repeat, but it certainly rhymes.

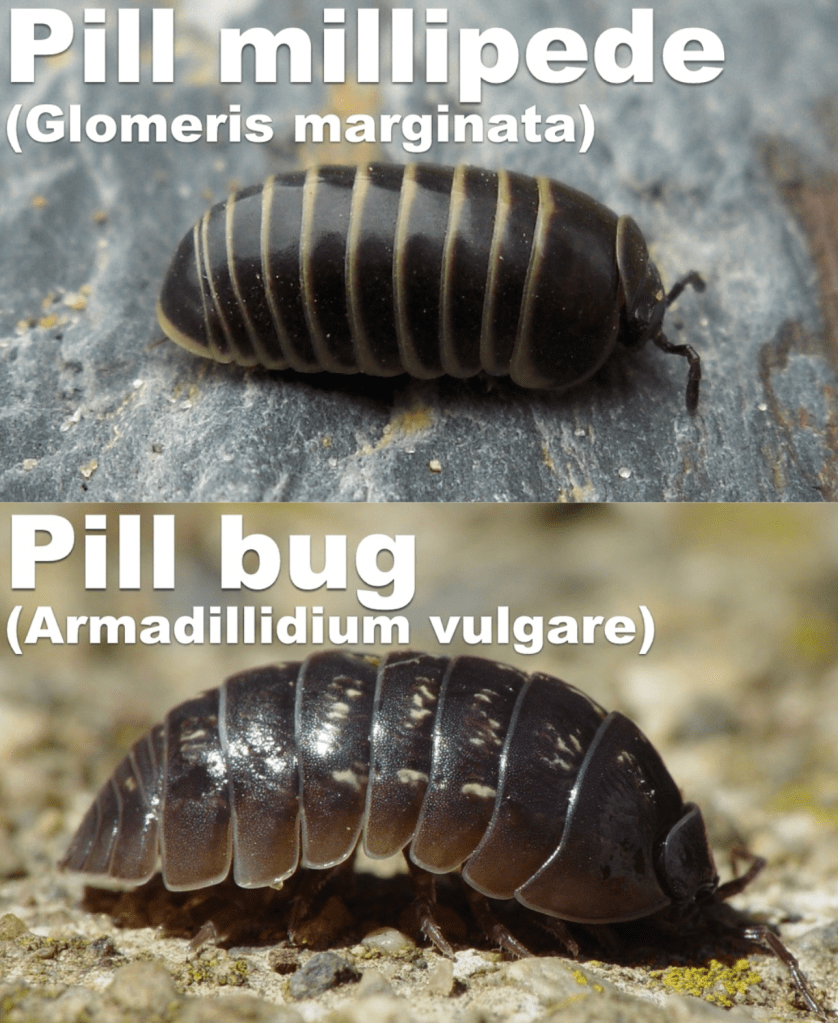

Convergent evolution has long been a problem for systematists as our instincts collide with nature’s tendency to land on the same solution time and time again. If homologous anatomy speaks the truth of shared ancestry, analogous anatomy is like a white lie confusing and frustrating our common sense. The large examples are famously fun: the moles of Australia appear to be the kin of the moles of North America despite being much more closely related to kangaroos and sugar gliders. But so are the small ones: the pill woodlouse and the pill millipede would be mistaken for each other by all but the most expert entomologist. This, despite more than 400 million years of divergence. The “pill” adaptation is a lot more common than you think!

In chapters eight and nine, Dawkins treats us to a reprised and reenergized defense of the gene-centric view of evolution by natural selection. Lest we debate the necessity of such a defense, he opens by providing its foil, so-called “biological relativity,” which was espoused nearly a century ago by Charles Singer and updated and repackaged for the modern era by Denis Noble. While Dawkins doesn’t exactly steel man the argument for biological relativity, he provides enough Singer and Noble quotations to do it justice and leave readers wanting of its mechanism. I’ll save you the search: there isn’t one.

Noble is famous for saying that genes are used by organs and organisms, but they do not encode organs or organisms, or words to that effect. As Dawkins points out, this is true but trivial. It is true genes do not control behavior, but only in the way your foot does not literally control the brake pads of your car. The fact that the process involves many complex intermediaries doesn’t change the status of your foot as the causal agent in the brakes halting the car. Declaring—smugly!—that the first domino doesn’t directly affect the last one is pure pedantry.

Dawkins’s defense of The Selfish Gene serves an important function beyond refuting biological relativity. The palimpsest of past lives is only comprehensible in light of DNA’s causal role in the diversity we see in nature. I am reminded of Dawkins’s own admission that, prior to Darwin, the watchmaker analogy would probably have convinced him of the existence of a divine creator.

But once life’s mechanisms were discovered, that belief became untenable. Life’s wondrous variety is made possible—and is truly encoded—by the digital information stored in DNA. And we now know that the DNA itself has layers to its information. Like the prose of a Dan Brown thriller, the epigenetic code sits atop the nucleotide sequence and can change what words mean without changing the words themselves. This is just like how the homographs tear and tear are rarely confused in context. We see in epigenetics another form of palimpsest, and the parchment is very much alive. Epigenetics adds complexity to DNA, but it does not supplant its central role in the mechanisms of life. The gene-centric view of evolution reigns supreme.

Even as epigenetics continues to dazzle, DNA’s complexity goes further still. Human beings have about 20,000 protein-coding genes, staggeringly few if you ask me. Estimates offered before the genomics era were an order of magnitude larger and, given how much more complex we are than bacteria, it’s easy to see why. But humans have twice that number of RNA genes, and this may be where the more recent evolutionary action took place.

Messenger RNA, or mRNA, is the only coding RNA, as this is the dutiful harbinger of DNA’s coded information. The remainder of RNA is therefore called noncoding, because its function is not limited to carrying protein-building instructions. Oddly named for what it doesn’t do, noncoding RNAs help cells use their genes in sophisticated ways. This is how organisms can get astoundingly more complex without needing more proteins. Indeed, chimpanzees and humans have almost all the same protein-coding genes and nearly identical versions thereof. However, the evolution of RNA genes has tweaked when, where, and how much these genes are expressed, tweaking the tissues and organs in turn. Small tweaks underpin profound changes and, once again, the responsible party is the molecular tinkering of DNA, that is, mutation.

A few years ago, my laboratory showed that a few random segmental duplications—a stuttering of DNA sequences that has littered our genome with pointless repetitions—had resulted in the crafting of new kinds of RNA out of old ones, which may have slightly altered the embryonic development of the human brain.

Though I was not witty enough to have articulated it so, the palimpsest is the perfect analogy. On top of a layer of repetitive gibberish, a new gene was imprinted. But the gibberish is easy to see underneath. Indeed, that was all we saw for decades. So that’s three layers to the genetic palimpsest. At least.

Although not explicitly discussed in this book, palimpsest layers can even be pieced together from small fragments, as has now been done with the genomes of Neanderthals. While many are aware we have sequenced these ancient genomes, what is not commonly understood is the computational ingenuity that allowed us to do it. Scientists now have access to genomes from long-dead human ancestor populations from all over the globe and at various periods of the distant past. Without the aid of a time machine, we can now piece together migration events, emergence of traits such as lactose tolerance, and gene flow among different human groups. The Genetic Book of the Dead indeed!

The interaction of behaviors and chromosomes is the subject of another of the book’s most fascinating sections—that on brood parasitism, the bizarre habit of birds laying eggs in another’s nest in an effort to commandeer parental care. While many species, especially waterfowl, do this to each other stealthily, there are some species so dedicated to the practice that they have evolved to do only this, the so-called obligate brood parasites. Because the whole species comprises freeloaders, they must parasitize the nests of other species. These devious thieves trick other birds into incubating their eggs and nourishing their chicks, even to the obscene extreme of a duped foster parent feeding a chick several times its size.

[You may remember that I wrote an article on brood parasitism for Undark/Smithsonian magazine a couple months ago.]

The common cuckoo is the most famous of the brood parasites, and it gets an extended treatment from Dawkins because there are several biological conundrums to resolve. There is deception and detection, in both the temporal and evolutionary senses, which harkens back to earlier sections on the biology of learning. There is also mimicry and camouflage, similarly drawing on an antecedent chapter. And there is a phenotype that seems impossible to have evolved.

Further still, the treachery of cuckoos provides a fascinating example of sexual diversity. It turns out that the female-specifying W chromosome encodes a signal that determines which type of eggshell the female cuckoos produce. Some shells closely mimic those of meadow pipits, and others mimic those of reed warblers. The two morphs are altogether dissimilar. And yet somehow the cuckoos have managed to mimic both through distinct matrilines. While males, with their ZZ chromosomes, are nonspecific and oblivious, female cuckoos are determined toward one line of mimicry or another through their W chromosome and, most fascinating of all, they appear to know which species their eggs will mimic!

Behavior and physiology are linked by a chromosome. This parallels a mirror example in the melanzona guppy, a popular aquarium fish, in which five distinct male morphs are triggered by five distinct Y chromosomes. These patrilineal “races” mate with females indiscriminately, keeping the gene pool thoroughly intermixed.

In illustrating how organisms are like windows into our own past, The Genetic Book of the Dead is a triumph. In many ways, it’s a sequel to The Ancestor’s Tale, with important updates for our metagenomic era. Entertaining, witty, and breathtaking in its scope, it could be written only by one whose knowledge of nature is as deep as his passion for it.

-NHL

Leave a reply to Mike Cancel reply